Universities must recognise that students are not little flowers who live on a cloud, but need to be exposed to a wide range of views that can prepare them for the outside world, argues Stefano Bonino

The discussion on free speech in British universities continues to inflame academic and public debates – not least in our own region. The National Union of Students (NUS) has received much criticism for hosting CAGE, an organisation run by former Guantanamo Bay prisoners and campaigning against the “War on Terror” at several university events.

The involvement of CAGE and other controversial speakers on campus draws our attention to the fragile boundaries that delimit free speech at the nexus between individual rights of expression and the collective responsibilities set out in the social contract. According to the latest rankings by Spiked Magazine, a strongly libertarian publication advocating for complete free speech, Sunderland University is the only institution in the north east to hold a green light for its “hands-off approach to free speech”. Northumbria University, Durham University and Teesside University all score amber for having “chilled free speech through intervention”, while Newcastle University scores even worse, red, for having “banned and actively censored ideas on campus”.

One of the most notable victims of restrictions on free speech is the former English Defence League leader, Tommy Robinson, who was banned from speaking at Durham Union last year. Robinson is just one of many controversial speakers who have been barred recently.

The axe of censorship has also fallen on the heads of conservative journalist Milo Yiannopolous and feminist writers Germaine Greer and Julie Bindel in October last year. Manchester University no-platformed Yiannopoulos and Bindel, while Cardiff University barred Greer from speaking on its campus. The Sun, blackfaces, men’s societies, homophobic, sexist and racist speech and adverts for pub crawls, sunbeds and payday loans have faced bans at some universities in the north east.

The boundaries of free speech are very fuzzy and escape clear-cut perimeters. While the government’s definition of extremism tends to broadly encompass a whole range of stances that are deemed contrary to British values, it would be naive to homogenise extremist views. Extremism is not a watertight category. Sympathising with the ideology of a violent jihadi group may fall short of direct support for, involvement in and/or glorification of terrorism but still warrants legal restraint in the interests of the public good. However, in a free society, it becomes all the more problematic to place legal restrictions on other extreme stances that run counter to both the views of the majority and the established democratic order but that fall short of direct support for and/or involvement in terrorist and/or subversive activities.

Controversial and unpleasant views are hard to properly assess and handle. Yet, our universities should recognise that students are not little flowers deprived of agency who live on a cloud. In a society that often does not conform to the politically correct bubble of academic circles, students need to be exposed to a wide range of views that can prepare them for the real life of the outside world.

Yet, between the two extremes – unchallenged free speech and censorship – there is a sensible option: regulation. Rather than banning or giving an open platform to highly divisive speakers, the NUS and universities across Britain, including the north east, should incorporate a principle of both regulation and differential treatment of controversial stances.

Regulation entails ensuring that panels include moderate and contradictory positions. Transphobic speakers, racist political figures and former Guantamano Bay prisoners should be challenged in open debates. Whilst universities are places of learning and uncomfortable conversations, they are not spaces for ideological indoctrination.

Controversial stances do not exist in a vacuum but are tied to political, social and historical contexts. Criticising government policies is legitimate and, indeed, a valuable exercise in shaping workable solutions to real world problems. But, in today’s fragile geopolitical climate, policy change will only be effected via moderate and credible action. As I recently argued with Chris Moos and Asra Nomani in the Times Higher Education, legitimate dissent has been fed into the mouths of highly problematic propagandists. When intolerant Islamists rile thousands of students against the British government, they perform a needless act of political resistance at a time in the history of Western civilization when societies are in search of unity rather than division.

Controversial as they are, Yiannopoulos, Bindel and Greer’s stances do not endanger the long-held values of our society: they should be openly debated rather than no-platformed.

Dr Stefano Bonino is a lecturer in criminology at Northumbria University.

Tell us your views in the comments section below – by clicking on the little speech bubble.

(Views expressed on our website and in our magazines and emails are not necessarily endorsed by The Northern Correspondent.)

Subscribe to our weekly email:

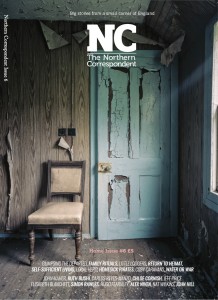

Buy our latest magazine: