Tom Keighley tells the story of the Durham village neighbours who died together at the Somme

“They were hard men. They took them out of the pit and put them on to the battlefield, just like that,” says Michael Burdon. For the last year, the 47-year-old fireman from Durham has been forensically tracing the story of his family members who fought in the Battle of the Somme.

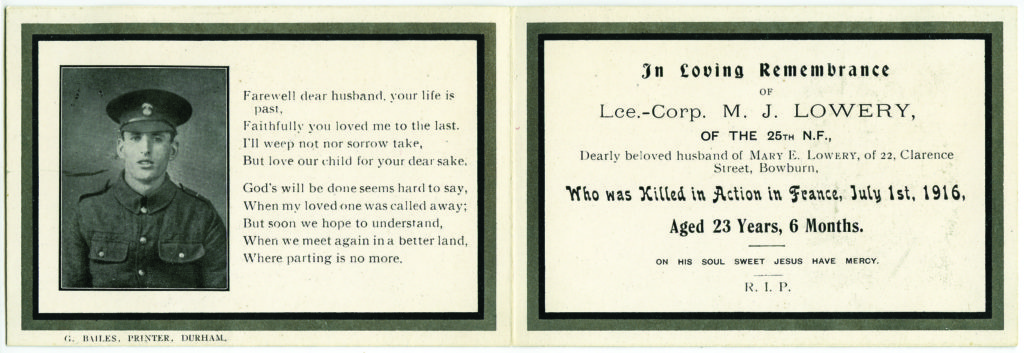

The story led him to the door of 22 Clarence Street in Bowburn – one of the pit village’s narrow terraced rows. It was here, in 1914, that Michael Lowery – Michael Burdon’s great, great uncle – moved in. He’d married Eliza McKeown and joined the family home, with John McKeown, his new father in law and James McKeown, his brother in law.

Born in Sligo on the west coast of Ireland in 1893, Michael Lowery came to England, and County Durham, with his parents John and Sarah. His father was a coal hewer and settled the family first in Hutton Henry and later Wheatley Hill, where young Michael joined him in the pit.

It’s likely they had a tough time of it. By the late 1800s, the Durham Miners’ Association counted several hundred first and second-generation Irish among its ranks, but they faced hostility from the local population who perceived them as imported strike breakers, here to take away work for lower wages.

The McKeowns’ house in Bowburn was state-of-the-art, for the time. The village was born just a little under eight years before the outbreak of war. Bowburn Colliery was sunk in 1906 and the clay excavated was used to make bricks for the neat rows of terraced houses that would house its workforce. They were among the first two up, two down style homes in the north east.

Accounts of colliery life from before the likes of Bowburn’s inception point to a cramped and dirty existence. A miner’s letter to the editor of the Durham Chronicle in 1865 describes homes at nearby Byers Green as lying next to “stinking muck heaps” where “one single room is the sole habitation of men, women, and five or six children”. As “foreigners” the Irish immigrants were typically housed in the poorest accommodation by pit owners. Historians suggest this only served to fuel the impression among indigenous north easterners that they were the instigators of such poor conditions, not the victims.

Number 22 Clarence Street would have borne the “knocker upper plate” stating the time its inhabitants were to be woken by the knocker upper’s rapping on the window. Together, John, James and Michael would make the short walk to the pit along with the 390 or so men who they would toil alongside each day.

One day in October or November of 1914, following the outbreak of war that summer, the three men of number 22 left Clarence Street for the North Road recruiting office in Durham – which opened between 8:30am and 8pm. They joined men signing up for all sorts of reasons – some to fulfil a desire for adventure, others out of national pride and many to escape laborious day jobs.

An article headlined “Splendid response from Durham” in an edition of the Durham Chronicle from the same month lists Michael, John and James among those proposed to join the Durham battalion of the Tyneside Irish. Their names feature next to men from the likes of Framwellgate Moor, Langley Park and New Brancepeth.

Alastair Fraser, an early printed books librarian at Durham University’s Palace Green Library, and a WW1 expert, suggests Michael had a strong motive for enlisting.

He says: “There were many reasons why men enlisted. Patriotism was a strong part of society, but to sign up with his young wife at home suggests he had real reason to do so.

“For a lot of men military service meant three square meals a day, two suits and a uniform for not that much more hard work than they were used to. I’m sure few of them thought they would be in it for anything like the four years it went on.

“Some of the men that joined Michael that day – the groups of relatives and friends – may have stood in the wrong queue. They’d be separated into different regiments and experience totally different wars from each other. Of course, some would never see each other again.”

Little is known about Michael’s reasons for enlisting in Kitchener’s New Army, though the sense of a looming German threat would hit home in the north east little more than a month afterwards.

In December 1914 Hartlepool was bombarded by the Germany navy. Hundreds of shells rained on the seaside town during a Wednesday breakfast time. The attack killed 130 and injured dozens more. An attack further down the coast at Scarborough, on the same day, spawned recruitment posters. “Men of Britain! Will you stand for this?” one asks, over a depiction of No. 2 Wykeham Street – reduced to rubble and with a caption counting the dead family of inhabitants.

Some four miles from Michael’s home in Bowburn, Durham City was beginning to look more like a city at war. The Waterloo Hotel on Old Elvet was used as a stables by the war department, and many of the buildings around the Market Place and Hallgarth were used as residential billets, offices and stores. It wasn’t unusual to see whole batteries of soldiers attending church parades or the odd airship passing overhead.

Michael, John and James were taken by train to Birtley where they trained. The men would buy their lunch from the town’s Co-op. They would occasionally join the Tyneside Scottish Brigade who were trained in the grounds of Alnwick Castle. Together they learned how to dig trenches at Blackfell Army Camp, on the site of what is now Washington Services.

From here the men moved to Salisbury Plain where they carried out manoeuvres before boarding a series of old ferries at Portsmouth for the crossing to France in January, 1916.

On June 8, Michael wrote to his sister Sarah at home. The letter is punctuated by an uneasy reference to guns heard from his position in the trenches, and his longing to see the recently born son he had yet to meet. He wrote:

“I don’t know what you will think of me not writing to you before now but with us been shifting so much you don’t get a lot of time but never mind better late than [n]ever you think I will get a surprise when I come home and see that little son of ours.

“Eliza tells me he is the picture of health but it’s to be hoped it won’t be long now before I get home to see him and you all it will be a big day when we all get home for good. I wish the time was here now and I’ll bet you are all wishing the same but we will wait ‘till it is God’s Will to end this War.”

The Tyneside Irish travelled to La Boisselle – a tiny village of 35 houses – in May. The British Tunnelling Company had been busy since November 1915 building a series of mine shafts around 95 feet deep that went under the German front line. It was packed with explosives.

At 7:28am on July 1, 1916 the explosives were detonated in a move to destroy German positions and block incoming fire. Reports from the time suggest the earth shattering explosion could be heard in London. For Michael it was the terrible signal that he was ‘going over the top’. Around 3,000 Tyneside Irish soldiers, many heavily laden with ammunition, shovels and rolls of barbed wire or signalling equipment on this blisteringly hot day, moved over no man’s land towards the German front lines. Their clumsy, ill-fitting tin hats slid down over their eyes as their boots fought for stable ground amid the rush.

At the age of 23, Michael was one of the 29,000 British soldiers killed on the first day of the battle that would last weeks. James, aged 24, was also killed. Michael Burdon isn’t sure how his great, great uncle died. Hundreds were cut down by German machine gun fire over what was supposed to be an unopposed stretch of land. Jackie Hunter, Michael Lowery’s neighbour from Bowburn, was shot in head while attempting to help his friend.

Michael and James’ bodies were never identified. Reports of the aftermath say the dead became sunburnt as they lay under the scorching hot sun. Like many miners, the Bowburn boys would have worn their identity tags around their braces on the waist – the same place they wore pit tokens at home in County Durham. Those sent to scour the battlefield afterwards were said to be from a southern regiment who sported identity tags around their necks and didn’t think to check the braces of their north east comrades.

John McKeown made it home. Like many who did, their world was dramatically altered. Alastair Fraser explained: “The history books focus a lot on those killed, but actually around 80 or 90% of men returned – and not a great deal is said about them. It should also be remembered that many men never went near the front line and never saw a German soldier. Their jobs were vital but they were not in mortal danger working in a mobile baths unit or a telephone exchange. Soldiers drove railway locomotives and piloted barges. Not everybody was in the infantry.”

“Many would return to places like Durham with profound psychological damage, physical injuries and having lost close friends and family. They returned to a harsh economic environment with little in the way of welfare support. Lots of men came back and had to resume their jobs, perhaps in the mines or shipyards.

“In my own research I’ve come across the story of German soldier who – like Michael Lowery – left a young pregnant wife in 1914, never got home leave and was killed in June 1915. It’s important to remember this was a European tragedy, not just a British one.”

At home, Michael Lowery’s wife Eliza was left widowed, and caring for his three month old son, named after him. Those living in the street chased away the postman as he tried to deliver the ominous telegram with a black band wrapped around it.

Michael’s death was confirmed in the Durham Chronicle in March of the next year. Eliza continued to live at 22 Clarence Street – which these days bears a bronze poppy in commemoration of Michael and James – and remarried exactly 30 years later. The house is one of 47 in Bowburn village adorned with the flowers.

Some 22 years later, many boys would see their fathers cry for the first time – for then it was becoming obvious their sons would have to go through it all again.

Somme 1916: From Durham to the Western Front – a new exhibition at Durham University’s Palace Green Library, runs until October 2, 2016.

This feature is taken from The Northern Correspondent #8 – we hope you’ll take a moment to buy a copy and read at your leisure. And if you value the kind of journalism we’re offering, please consider helping us to sustain it by taking out a subscription to the magazine.