The cost of Freedom of Information requests is a price well worth paying for transparency in the north east, argues Mark Blacklock

Somewhere in this region there was – there still may be – a superintendent registrar of births, deaths and marriages who doesn’t like journalists.

This may be my fault. She may have been predisposed to hate reporters, but when she asked why I wanted a copy of a birth certificate, and I said it was none of her business, it can’t have helped.

I paid for my smart-mouthed remark with a day-long delay, but eventually got what I wanted because she couldn’t stop me. I have a right to that sort of information and I have a short fuse with officials who try to stop me.

What this illustrates, other than my lack of tact, is that the default position of many public officials is to ask, “Why do you want to know?” It reflects a culture in public and civic society of bias towards secrecy and against openness. This will be reinforced if the current rules are tightened and not loosened. Fifteen years after the Freedom of Information Act was born, it is being reviewed by a panel of people already on record for criticising it. The process is overseen by the Cabinet Office, the government department with the worst record for responding to FoI requests.

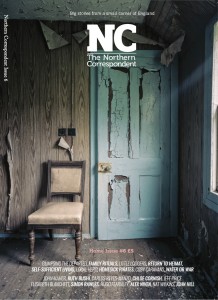

Photography by Kim Hoaxashian, under Creative Commons licence

Should we care if the law is weakened? What has the Freedom of Information Act ever done for the north east?

Well, we know a hospital trust spent £10m on consultants for cost-cutting advice, another paid £907 for an agency worker’s 11-hour shift, and two councils shelled out more than £1m compensation for slips and trips.

Regional journalists learned that 10-year-olds were “sexting” classmates, police were physically unfit, a council’s £480-a-day tourist bus carried just three passengers, and an open air concert lost a cash-strapped authority £60,000. They uncovered ambulance delays, the cost of murder inquiries and how violent criminals and sex offenders applied for school jobs.

Stories exposing wrongdoing, corruption, incompetence or criminality – or just shedding a light on how our money is spent – are in the public interest. We would know nothing without the Act. Objectors say FoI is expensive and used for frivolous “fishing expeditions”, though personally I feel better for knowing someone in the region keeps a zebra or a crocodile at home, and that Hebburn is the north east’s capital for wedding punch-ups. As for cost, it’s a price we pay for transparency.

So how far do we go?

What about people’s pay? Asking how much someone earns is like asking how often they have sex. You won’t get an honest answer. But if they run a council, I think I’m entitled to know the size of their (pay) packet.

Want to know how much I earn? Something north of £30 an hour, depending on which university I’m teaching at (it could be one of four). You’re entitled to know, as these places are part funded by your taxes (unless you’re Google, Starbucks, Facebook, Bono or a Rolling Stone). It’s the same reason we know about university vice chancellors’ salary and perks. We are entitled to know this stuff as citizens. Journalists are watchdogs, a bridge between the public and the public servants they hold up to scrutiny and account.

Want to know how much I earn as a media consultant and freelance journalist? Mind your own business. Unless of course you want to hire me, and then I’ll be glad to give you a quote – and, if you represent a public body, free to tell any passing taxpayer who asks. It is, after all, their money and their business.

Mark Blacklock is a journalist and university lecturer. You can follow him on Twitter.

Tell us your views in the comments section below – by clicking on the little speech bubble.

(Views expressed on our website and in our magazines and emails are not necessarily endorsed by The Northern Correspondent.)

Subscribe to our weekly email:

Buy our latest magazine: