Certain types of crime story dominate our local newspapers and TV bulletins, while other types of danger that could prove more of a threat to us may be under-reported, argues Mike Rowe

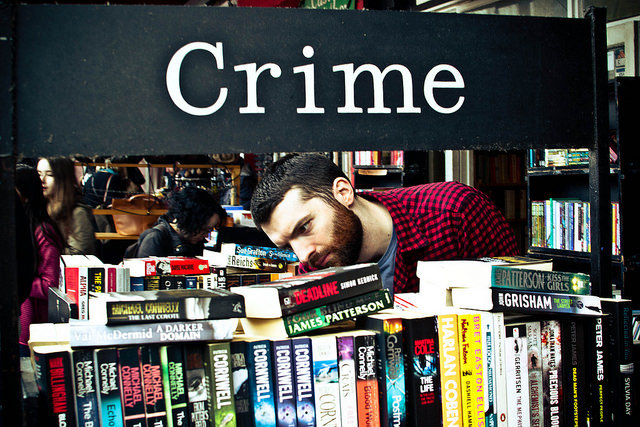

Local media is – and always has been – obsessed with crime stories. Whether a nightly TV broadcast or a morning tabloid, our news media devote more time and space to crime reporting than to most other forms of news, sport, current affairs, or human interest stories. Journalists and editors work to the principle “if it bleeds … it leads”, indicating that gruesome content is likely to promote stories up the news agenda.

Other factors that shape the newsworthiness of a crime include the characteristics of the victim, any peculiar or unusual features of the incident, the extent to which it might be part of a series or sequence of crimes, and links it might have to wider social concerns already established in the media. Gang-related offending, for example, might not be especially serious relative to other offending but often meets many of these criteria, and so is more likely to be reported than, for example, white collar fraud.

Why does crime feature so heavily in media coverage? In practical terms crime stories are often easy to cover, relative to other issues. Police make appeals for witnesses, “tip off” journalists (sometimes in ethically problematic ways), court hearings are easy to access and scheduled long in advance. Equally, readers and viewers are avid consumers of crime reports.

Photograph by Joseff Thomas, under Creative Commons licence

And perhaps it’s because they provide vicarious pleasure: an insight into experiences and aspects of life unfamiliar to many of us. That crime (especially murder) features so strongly in popular culture, and has done so throughout much of human history, suggests that we are in some way fascinated by such behaviour… even while finding it morally repellent.

There are several discernible impacts of this fascination. In particular cases, of course, the media can encourage witnesses and victims to come forward. Recent historical sexual abuse cases have demonstrated this. The media can, as in the case of Raoul Moat in Northumberland in 2010, be used by police to communicate with the public and to try and provide reassurance. In more general terms the impact is less clear. On the positive side, it might be that the media coverage of violent crime, especially murder, reflects social norms that continue to find such actions reprehensible.

So it’s a good thing that these events tend to be reported heavily: it would reflect badly on wider society were such crimes so commonplace and unremarkable that they passed by unreported. Furthermore, covering crimes such as domestic violence or sexual abuse might help other survivors by eroding stigma and stereotypes about such offences.

However, disproportionate media focus on crime, especially violent offences, can raise fear and anxiety to levels that outstrip real risk. Particularly high-profile offences reported by the media are usually rare – objectively we are unlikely to become victims of these offences – and yet the types of harm and danger that might prove more of a threat to us go relatively under-reported. White-collar, corporate crimes, crimes against the environment, health and safety violations, and so on, remain relatively under-reported in the media considering the impact they have on the public.

Media coverage can also sustain stereotypes of victims and offenders that also have negative implications for the wider social groups that are misrepresented (young people, for example) and can also misdirect attention from more significant sources of danger.

What remains much more difficult to identify is the impact of social media as “citizen journalists” create their own coverage of crime. As in other respects, the changing media landscape will have implications for crime reporting. It seems unlikely, though, that the obsession with crime stories will diminish.

Mike Rowe is a professor of criminology at Northumbria University. You can follow him on Twitter and he is one of the speakers at tomorrow’s Crime Story festival (Saturday 11th June) for crime writers and readers, organised by New Writing North and Northumbria University. For last minute tickets, contact Laura Fraine.

Tell us your views in the comments section below – by clicking on the little speech bubble.

(Views expressed on our website and in our magazines and emails are not necessarily endorsed by The Northern Correspondent.)

Subscribe to our weekly email:

Buy our latest magazine: