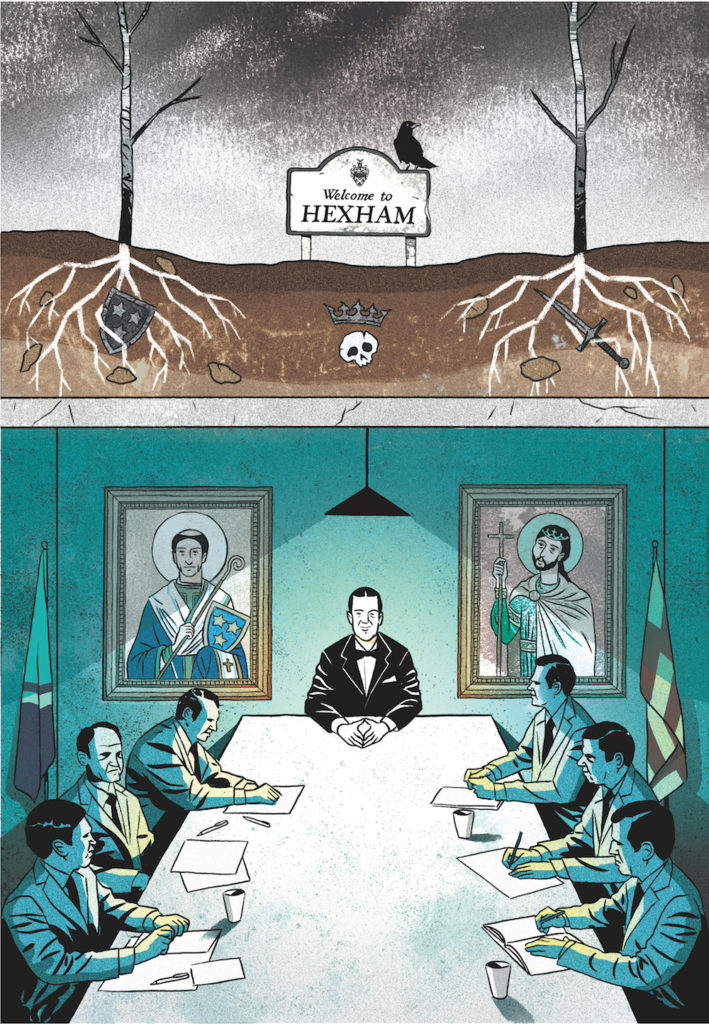

Harry Pearson retreats to Hexham in search of the nuclear bunker from which the post-apocalyptic north would have been ruled. Illustrations by Leigh Pearson

Sunday morning on board the westbound train from Newcastle. The pony-tailed Cumbrian conductor makes his announcements in a melancholic, sing-song voice that suggests Eeyore reciting Rimbaud. When he tells passengers that “Any items left unattended/ May be removed/ And destroyed/ By the British Trans/ Port police” it sounds less an issue of public safety than a mournful comment of the transience of human existence.

At Hexham (“This is/ Your final/ Station/ stop”) the train disgorges a disparate clutch of travellers. Haredi Jews from Gateshead, Muslims from Fenham, Poles and Romanians, all making their weekly voyage to the town’s car boot fair; divided by culture and language, united by the hunt for bargains – a toasted sandwich-maker that just needs a plug to be as good as new, a jigsaw with some key pieces missing, a Barbie doll with leftover traces of biro eyeliner.

As they cross the bridge over the railway, past the mini-roundabout, towards the cattle mart – the overflow carpark already nearing capacity – it’s unlikely any of them glance to the left, to the long strip of waste ground, flanked by a car dealership and the back of Tesco, squeezed against the embankment of the Carlisle line. There’s nothing here to draw the eye, after all. Swathes of willow herb, a few rusting lumps of iron, what appears to be a disused gravel pit filled now with ash and sycamore trees, the occasional rabbit. Few who look at this unprepossessing scrubby field would suspect that it was once the location of a building from which the north would be ruled, occupied by a hand-picked elite, commanded by a figure of absolute authority whose word was law and at whose discretion the guilty could be flogged or hanged.

We do not speak of King Oswald of Northumbria, who destroyed the pagans at nearby Heavenfield, nor of Saint Wilfred, Bishop of Hexham whose retinue of knights was “greater than that of any prince” nor even the ferocious John Forster, Warden of the Middle March. No, this was a far more shadowed character: Commissioner, Region One. A figure who would have been summoned to Hexham by a single word, “Tarpon” and would have arrived in Tynedale certain that, barring some diplomatic miracle, civilization as mankind understood it was on the eve of destruction.

Because this wasteground is the last remains of the plan to turn a Northumbrian market town into the capital of the north, the site of RSGC 2.2, one of the nuclear bunkers from which post-apocalypse Britain would have been administered. By then, it was predicted, London and the Home Counties would have been obliterated. For the first time since King Æthelstan unified England in 927, the north east would have been left to its own devices. It says much for the enduring centralisation of British government that the only people ever really likely to give autonomy to our region were Nikita Khruschev and his successors in the Kremlin.

The plan that would lead to Hexham becoming putative capital of North Yorkshire, Durham and Northumberland was formulated by the Bishop Committee in 1958, a response to “Ace High”and “Cloud Dragon”, two top secret studies of the effects of a Soviet nuclear attack on the UK. (British codenames of the period generally exuded a kind of damp and tweedy old school tie-ness that at times teetered close to parody. Subsequent Civil Defence Force nuclear exercises would be named “Scrum Half” and “Short Leg”. The nation’s intercontinental ballistic missile system – tested 30 miles west of Hexham at Spadeadam – was “Blue Streak”.)

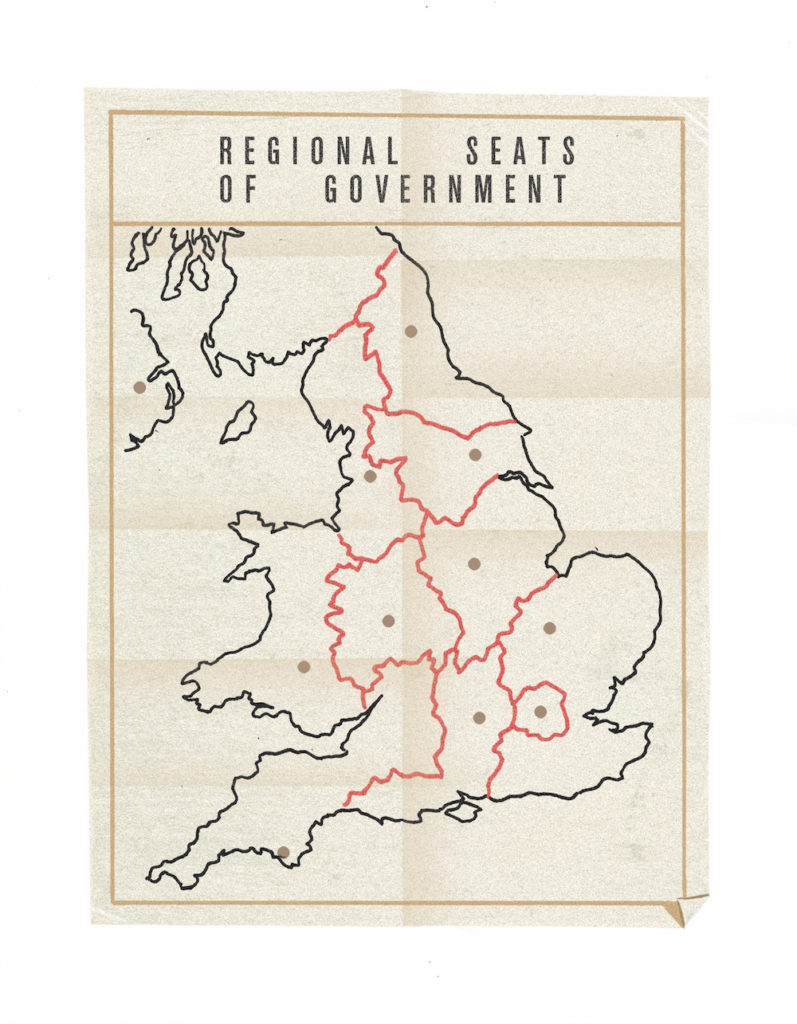

The Bishop Committee concluded that after the dropping of the USSR’s H-bombs “central government would cease to exist” and that power should therefore be devolved to sixteen regions. Purpose built nuclear bunkers should become Regional Seats of Government (RSGs). Hexham was named as the capital of the north (confusingly the North East Region consisted of the East and West Ridings of Yorkshire. Its RSG was to be at Shipton). Harold McMillan’s government accepted the recommendations without demur. They codenamed the new top secret scheme “Programme X”.

Under Programme X, Hexham was to have a nuclear bunker designed to withstand a 500 kiloton bomb landing five miles away (perhaps the assumption was that, in a fit of class rage, the Soviets would target the upmarket village of Corbridge) and house close to 400 staff with supplies for 30 days in an internal space measuring 57,000 square feet.

Under Programme X, Hexham was to have a nuclear bunker designed to withstand a 500 kiloton bomb landing five miles away (perhaps the assumption was that, in a fit of class rage, the Soviets would target the upmarket village of Corbridge) and house close to 400 staff with supplies for 30 days in an internal space measuring 57,000 square feet.

The regional commissioner for the north – at whose discretion both capital and corporal punishment could be administered to looters, rioters and others who regarded the end of the world as an opportunity for criminal antics – was to be the minister of transport. In the early 1960s that would have been Ernest Marples, the Conservative member for Wallasey (Angela Eagle’s current constituency). Marples is perhaps best remembered for implementing the Beeching cuts to British Railways, admitting to using prostitutes during the Profumo inquiry and absconding to Monaco to avoid a large tax bill. Clearly he was just the sort of man to flourish when civilization collapsed.

Hexham’s bunker was slated to cost £2 million (around £27 million today) and was due for completion by 1965. In the meanwhile the RSG would be housed at Gaza Barracks, Catterick which had itself supplanted the barracks at Kenton Bar. According to some modern Cold War researchers, the Hexham bunker was completed sooner than expected – in 1961. If that is the case then its location is a secret so closely guarded that nobody seems to know where it is, or was. What is for certain is that when “Spies for Peace” published its infamous list of the top secret RSG sites during the Aldermaston March of 1963, the north’s bunker was still Gaza Barracks.

On Sunday morning, as the car boot traffic backs up along Rotary Way, I stroll up the bank to JD Wetherspoon to meet a retired police officer who is taking advantage of the free coffee refills to spend a morning in the pub. “I can just turn the heating off,” he says. “Sit here from 9.30 till lunchtime. Saves me a fortune in winter.”

As one of the senior police officers in the town during the 1960s, he was trained as part of a Civil Defence Force that once numbered 330,000. Even he does not know anything about the Programme X bunker.

“When the Russians invaded Afghanistan it all kicked off again,” he says, nodding to a former colleague who is just sitting down to an all-day breakfast, “You remember there was that Protect & Survive leaflet got stuck through your letterbox? Aye, well, Thatcher brought in expanded plans for home defence. That was when they started doing up the old MOD store for Zone HQ.”

He points out of the rear window of Wetherspoon’s in the general direction of the tatty strip of waste ground. Until 1994 this spot was occupied by a massive windowless building of brick and concrete. The structure had originally been a WW2 strategic meat store. In the early 1980s, under the new government policy, it had been strengthened using brick, concrete and steel, designed to house 180 officials who – under control of the Home Office (themselves tucked away in a deep bunker of their own) – would be expected to run the north east.

“To be honest it was useless,” the retired police officer says. “I had a mate was one of the civil engineers worked on it. He said it wouldn’t have survived any kind of blast, and even if it had, the electrics would have blown out.”

The Soviet bloc collapsed, the Cold War ended. In 1994 the bunker was demolished. “It was all just propaganda, really, make people feel better. The Russian plan wasn’t to drop bombs directly. They were going to detonate them in the North Sea, send a tidal wave washing over the coast and into the water supply. If you weren’t drowned, the radioactive water would have poisoned you.’

He gets up and waggles his mug: You want another top up?”

[…]

Read more in The Northern Correspondent #9