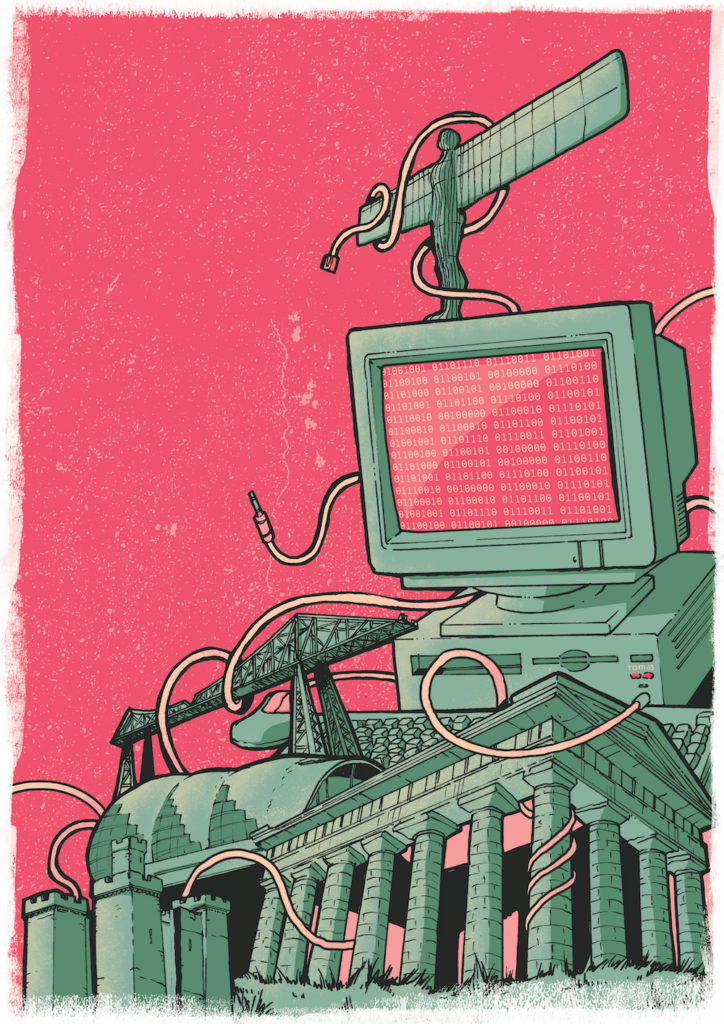

Julian and Sarah Hartley study the invisible power of algorithms shaping our northern identity. Illustration by Tom Boyle

News of the EU referendum result spread quickly across social media. While the cheering woman hoisted on her partner’s shoulders at the Sunderland count became the image of the night on a near constant loop over broadcast media, your online experience of the result might not have seemed quite so jubilant.

If you were a Remain voter, maybe it was almost silent. As Tom Steinberg, the founder of transparency organiser My Society observed soon afterwards, there was something very noticeable missing in his social media feeds after the result.

“Am actively searching through Facebook for people celebrating the Brexit leave victory, but the filter bubble is SO strong, and extends SO far into things like Facebook’s custom search that I can’t find anyone who is happy despite the fact that over half the country is clearly jubilant today and despite the fact that I’m actively looking to hear what they are saying,” he said.

What Steinberg and many others experienced in the aftermath of the EU vote was tangible evidence of the power of algorithms, those lines of code that now shape our every online click and move.

Sometimes they can seem benign, almost invisible, to our movements – maybe the uncanny way an advertisement for something you’re seeking will suddenly catch your eye on Facebook. But whether you notice them or not, that secret code will be shaping the way you see the world.

At some level you could find it reassuring to have your views re-inforced in this way; after all, feeling part of the crowd can be comforting. But it also raises many problematic, and potentially dangerous, questions for us as a society. Extreme views can feel normalised and behaviours previously considered unacceptable can find their like-minded participants on this global stage.

The author of The Filter Bubble, Eli Pariser, questions how far Google’s data-crunching algorithm goes in harvesting our personal data and shaping the web we see accordingly.

He argues that this will ultimately prove to be bad for us and bad for democracy. “As web companies strive to tailor their services (including news and search results) to our personal tastes, there’s a dangerous unintended consequence: We get trapped in a ‘filter bubble’ and don’t get exposed to information that could challenge or broaden our worldview.”

In a TED Talk, Pariser demonstrated this effect by asking people to take the search term “Egypt” and share a screengrab of their results. The personalised nature of the results meant one person’s search returns had Egypt as a place of crisis and protest while another was presented with travel and encyclopaedic information; Egypt as a holiday destination and tranquil escape.

When we repeated the experiment using the search term “Newcastle” we achieved similar results where the location of the person searching made a difference. Overseas searches offer travel deals while search from the UK returns football related content.

But while it’s interesting to think about, and demonstrate, the filter bubble at work, the impact it has on life in the north east, and even the way people think about the region, are being altered and affected in ways we don’t always understand. Yet this largely invisible power is slowly emerging as a topic of public discourse.

As the activities of algorithms are so deeply embedded into our everyday experiences, questions arise about the motivations and integrity of those with the power to create them.

Founder of the Kaleida Networks online analytics platform and Guardian columnist Matt McAlister makes the point that “Algorithms aren’t monsters” and asks us to see the opportunity to take charge of them: “Think of them more like puppies. They want to make you happy and try to respond to your instructions. The people who train them all have their own ideas of what good behaviour means. And what they learn when they are young has a profound effect on how they deal with people when they’re grown up.”

But, he notes, there is currently a gap between the knowledge of those wielding the power and those we look to in the civic sphere. “As policy folks get their heads around what’s going on they are going to need some language to deal with it.”

The policy deficit which McAlister refers to points up a potential void in governance. Could we unwittingly be delegating power influencing the public image of the north east to lines of code?

When we consider the social effect of filter bubbles, it can seem that experience of places is becoming increasingly personalised and therefore less public in the sense that shared experience is less likely.

As Manuel Castells, the great sociologist of our network society, wrote: “Since shared experience is less and less shared, and we live in a society structurally destined to an ever-increasing individualisation of communication processes, we are witnessing the fragmentation of communication systems and of the codes of cultural communication existing between different individual and collective subjects.”

When his line of thought is followed, the notion that a concept of “northernness” means different things to different people has never been truer. It might be that this fragmenting of what the north means has generated a moment to question if a collective northern identity and memory is under threat?

The custodians of that memory are the museums, libraries and archives of the region and their mission is to help people determine their place in the world and define their identities, so enhancing their self-respect and their respect for others.

Today online discovery of archives is mediated by algorithms, and this mediation is changing the public experience and discovery of archive holdings. But at what cost?

We talked to the digital programmes manager at Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, John Coburn, who is responsible for the algorithms which arguably exercise some of the power over northernness. The archives are the preserve of traditions, cultures and memories, a repository of northernness if you like. The whole system of public archives is an exercise in power: the materials they collect, the public access they offer, and memories these trigger are powerful processors of regional identity and collective consciousness.

In order to facilitate online discovery of 32,000 diversely eclectic artefacts, Tyne & Wear Archives has come up with a way to explore the collection that is beautiful in its disruption of the filter bubble (and thankfully non-technical and easy-to-use).

Alongside a standard searchable database, visitors to their website are invited to “dive in”, discovering the collection of archive materials through infinite possibilities. The archive reveals itself in a way that is sometimes surreal and feels serendipitous due to a generated network of connections linking objects which lead the user on a journey in space and time of discovery.

It’s not unlike the Improbability Drive featured in Douglas Adams’ Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. According to Adams, the Improbility Drive “passes through every conceivable point in every conceivable universe almost simultaneously.” In other words, whoever uses it is “never sure where they’ll end up or even what species they’ll be when they get there”.

With a vast collection to draw on, the serendipitous discovery that the team has built into the experience should mean it’s a long time before boredom sets in. “It is a serendipitous interface but it isn’t a byword for randomness. Audiences generally dislike pure randomness” says Coburn.

Whether you, not-so-accidently, discover the bones of animals dredged from Tyne mud, algorithms are making the connections between you and the north east without you actively seeking them.

Coburn talks of antlers, a shopping receipt from Fenwicks in the 1930s, and hints to the very real possibility of a heartfelt letter to someone unknown from a relative that might just be part of your family. Thanks to social media, our serendipitous archive experiences of these objects becomes public and so the sharing continues to forge connections. In a sense, northernness materialises through the materials that trigger memories and relationships that make us public to those who can relate to that experience.

He argues the work thathe and his colleagues do will lead to algorithms which don’t close down exploration, and collective experience but instead inspire new pathways. But in other areas of life, maybe the power shift has reached a point of no return?

Steinberg certainly thinks so and urges those with influence to fight back against the tech giants: “This echo-chamber problem is now SO severe and SO chronic that I can only only beg any friends I have who actually work for Facebook and other major social media and technology to urgently tell their leaders that to not act on this problem now is tantamount to actively supporting and funding the tearing apart of the fabric of our societies.

“Just because they aren’t like anarchists or terrorists – they’re not doing the tearing apart on purpose – is no excuse. The effect is the same. We’re getting countries where one half just doesn’t know anything at all about the other.

“It’s in the power of people like Mark Zuckerberg to do something about this, if they’re strong enough and wise enough to swap a little shareholder value for the welfare of whole nations, and the world as a whole.”

[…]

Read more in The Northern Correspondent #9