There has been too little debate about the usefulness of referendums, says John Tomaney, who led the Yes campaign in the vote on a northern assembly

Why do we use referendums to address political questions? The idea of a referendum as a way to settle contentious political issues is a relatively recent innovation in the British constitution. It was only in the 1970s that referendums began to be used in the UK. Local referendums were held on prohibition in Scotland after 1913 and on pub closing hours in Wales, while the Oxford jurist and academic, A.V. Dicey, made the case for referendums as far back as 1890.

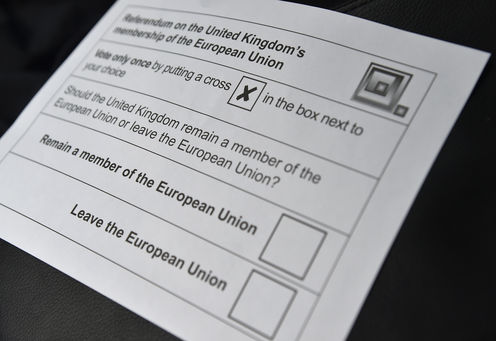

The modern history of referendums began with the “border poll” on Northern Ireland’s membership of the UK in 1973. This was followed by the referendum which confirmed Britain’s membership of the European Community in 1975 and then by referendums on the Scottish and Welsh devolution in 1979, but it was to be another generation before they were used again.

Referendums have been much more widely used elsewhere, including extensively in Switzerland since 1874. A referendum approved the Irish constitution in 1937. Since then there have been 35 referendums to approve or reject amendments, including votes on divorce and abortion, the rights to which were restricted by the constitution.

Thousands of referendums have been held in the United States under the provisions of different state constitutions. Referendums have been part of the constitution of California since 1849 and many state elections are accompanied a list of “ballot propositions” on a wide range of subjects.

Referendums come in many shapes and sizes around the world. Unlike in the UK, citizens in some countries, such as the Netherlands, are themselves able to initiate referendums through mechanisms such as petitions. In some countries there are thresholds on turnouts. For instance, voters in Portugal in 2007 supported an extension to abortion rights, but because the turnout was less than 50% the result was declared void, although the Portuguese parliament later legislated on the matter anyway.

New Labour created the contemporary fashion for referendums in the UK. Referendums were held to create a Scottish parliament and a National Assembly for Wales in 1997, the mayor and assembly for London and the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland in 1998 and the north east assembly in 2004. Thirty seven local referendums were held on proposals to created elected mayors between 1997 and 2010 with turnouts ranging from 10% (Sunderland, 2001) to 64 % (Berwick, 2001 – but there the vote took place alongside the general election). Most of these referendums rejected the proposed change, while in a few cases a second referendum has been led to the abolition of the office of mayor.

There has been surprisingly little public debate about the usefulness of referendums. They have been used since the 1970s in an attempt to settle constitutional questions, although in inconsistent and even capricious ways. The proponents of referendums claim they possess a range of advantages. It is argued that referendums enhance existing forms of representative democracy, providing an addition to the deliberations of Parliament. This argument might seem strong in an era when faith in party politics appears to be diminishing.

Referendums might be expected to settle contentious constitutional issues, but the experience of EU membership and Scottish devolution demonstrate that this is not always the case. In the eyes of some, referendums provide opportunities for citizens to engage more directly in politics and raise the level of knowledge about important issues.

The referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 certainly captured the popular imagination and generated debate, at times virulent. It seems doubtful though that the vote on the elected mayor of Sunderland did much to stir the still waters of political debate there. The Brexit referendum was hardly democracy’s finest hour as factions of the Tory party traded insults with each other and misinformation with the public.

Referendums come with problems. How can complex constitutional questions be reduced to simple “Yes” or “No” answers? Can citizens reasonably be expected to grasp arcane technical details? Citizens may end up voting on matters other than at hand, perhaps to punish the sitting government. In the north east assembly referendum, the modal explanation for voting “No” was lack of understanding of the issues. In the UK, at least, referendums as means of engaging citizens and deepening their knowledge of politics seem to be more the exception than the rule. Referendums more likely involve elite groups – politicians, media and wealthy individuals – trading unverifiable “facts”, as exemplified by the Brexit referendum.

In this context, the truth may be hard to find. In the 2004 referendum on the creation of a north east assembly, opponents of the proposition consistently claimed that an assembly would lead to more politicians, although the proposals actually involved a net reduction in their number. Nevertheless, this “fact” was widely believed by voters and “No” campaigners seemed to take great pride in the fact that they had confused voters on this point. Many referendums have been used not to enable change, but to stymie it.

As the number of referendums proliferates, there is evidence that citizen enthusiasm for them diminishes. Switzerland is seen as providing best practice in direct democracy in Europe through its extensive use of referendums at the cantonal and national levels, but voter turnout there has fallen significantly recently.

Perhaps the biggest weakness with referendums in the UK concerns the way they are used (or not used) for tactical advantage by governments. Although the conduct of referendums is regulated by the independent Electoral Commission under the provisions of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act, 2000, governments have substantial discretion on which matters are subject to referendums and the timing of them. This is not typically the case in other jurisdictions where the constitution stipulates the conditions under which referendums are legitimate.

The decision to hold the first UK-wide referendum – on membership of the European Community in 1974 – was taken largely to manage divisions inside the ruling Labour Party. Plus ça change. The current referendum on membership of the EU owes much to David Cameron’s desire to manage longstanding and bitter divisions within his own party and to neutralise the threat of UKIP. That this strategy has backfired spectacularly does not negate its origins. Similarly, governments can choose not to hold referendums, if it suits them, even if the case seems compelling. For instance the current Conservative government announced a “devolution deal” for the north east, which required the region to accept a directly-elected mayor. This deal, which the government claimed (implausibly) was “historic”, was negotiated in secret with local government leaders and there was no suggestion that voters in the region should have a vote on the proposal.

In 2010, a report by the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution concluded that “The balance of the evidence that we have heard leads us to the conclusion that there are significant drawbacks to the use of referendums. In particular, we regret the ad hoc manner in which referendums have been used, often as a tactical device, by the government of the day.”

It is now hard to imagine a future without referendums and they may serve a useful purpose, given the low regard in which our democratic institutions are held. But there is strong case for determining on a much more rigorous basis why and when they should be used. Referendums reflect a winner takes all approach to politics. But shouldn’t our future be about finding ways to agree, rather than ways to entrench our differences?

John Tomaney is professor of urban and regional planning at University College London.

Tell us your views in the comments section below – by clicking on the little speech bubble.

(Views expressed on our website and in our magazines and emails are not necessarily endorsed by The Northern Correspondent.)

Subscribe to our weekly email:

Order our latest magazine:

Pingback: Jo Cox | Alexander Coop

It should be that we try to understand differences and this helps to form a better future for everyone.

“Winner takes all” illustrates the false ideology of competition.

On Thursday 23rd June, I did not go to bed and wake up to the result of the vote.

I stayed up all night, watching each result, noting the numbers, hearing the talk from those who do not seem to deal with the public in local shops, local buses or just speak and help when necessary other humans who need help and reassurance. Perhaps this is the problem in society today-looking out to another person and seeing what goes on in the world beyond ones self. Looking out to the town, where people go for pleasure, for comfort for a job. Then looking further to the region and the nation and the continent and world, seeing the needs of people to feel secure and to connect with each other. The consumer world encourages the differences in humankind-that is what makes profits, but distracts from a lot from forging empathy and true community -which is so badly needed at the moment.

On Thursday 23rd June, I did not go to bed and wake up to the result of the vote.

I stayed up all night, watching each result, noting the numbers, hearing the talk from those who do not seem to deal with the public in local shops, local buses or just speak and help when necessary other humans who need help and reassurance. Perhaps this is the problem in society today-looking out to another person and seeing what goes on in the world beyond ones self. Looking out to the town, where people go for pleasure, for comfort for a job. Then looking further to the region and the nation and the continent and world, seeing the needs of people to feel secure and to connect with each other. The consumer world encourages the differences in humankind-that is what makes profits, but distracts from a lot from forging empathy and true community -which is so badly needed at the moment.